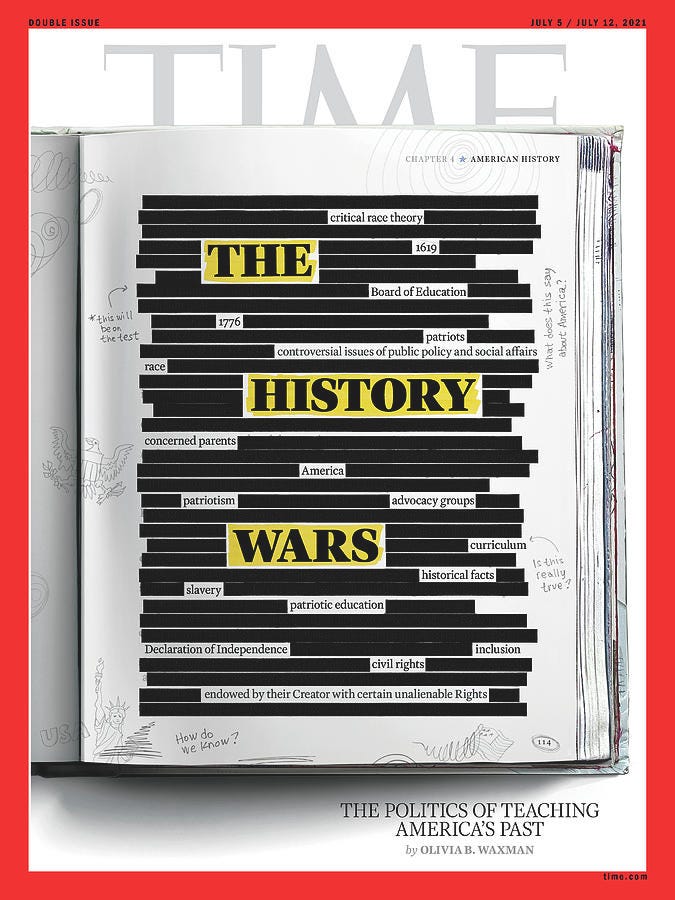

I hope you will indulge me in a personal reflection on a journey that I’ve been on. The past year has been an opportunity for discovery in the arena of history and teaching. I have learned much in the past year by entering the “history wars.”

Allow me to explain.

I am a retired history teacher. I taught history to hundreds, if not thousands, of young people from the late 1970s until the mid-2000s. I always taught American History from a perspective of honesty and inclusion of diverse stories and people. Yet, using the old textbooks and curriculum from decades ago, the narrative was grounded in a white supremacist view of US History.

I was never fully comfortable with that perspective.

The last group of students I taught was in 2007. For a few years, I worked as an education consultant for a non-profit ed-tech organization. I taught teachers and administrators how to navigate the rules and requirements of “No Child Left Behind” and later, “Every Student Succeeds” during the Bush and Obama years. It was a job, and I did enjoy it, especially the coast-to-coast travel.

But history always flowed through my mind and my imagination. It was my first love.

Between 2007 and 2022, I set out on a private journey to learn more about the history of racism and enslavement in the United States. Through a personal transformation, wrought from reflections on the histories I read, and travels to historical sites, I began to develop a new view of how to teach US History. I had always taught about these events, but never from the perspective of one who holds responsibility for changing the legacy and outcome of that terrible era of enslavement and Jim Crow, and telling the truth about it.

Finally, I wrote a book about my new discoveries in 2024. The book is titled The Spiritual Journey to Antiracism: A Travel Guide for White People. The book is full of historical accounts of enslavement and those who fought for their freedom. However, it also recounts my personal journey out of an apathetic non-racism to a more activist anti-racism stance. My life has not been the same since.

Last year, an opportunity arose for me to become an adjunct instructor in American History at our local community college, so I was excited about the possibilities. Here was a second chance to tell the story straight up, no holds barred, and expand the narrative beyond the white-centered versions of the past.

It almost felt like I was starting my career over again, like a first-year teacher. It had been fourteen years since I had a group of young people in a formal classroom setting, so yeah, I was a little nervous. But the nervousness was more about changing the way I used to teach United States history to a more inclusive and honest one. How would students react? After all, this is a rural area in the Midwest and is ruby red.

You see, I have always taught about slavery, but now I want to teach about enslavement. Language is meaningful, and I wanted to be sure that students understood that Africans were not slaves; they were put into slavery or were enslaved.

I wanted to teach about the origins of Euro-American bigotry starting from the Doctrine of Discovery in the 14th century. That doctrine paved the way for an “American Holocaust” of massive proportions. It allowed an unprecedented colonization, genocide, and land-grab from Indigenous peoples of the Americas. It became the motivation for Manifest Destiny in the 19th century and the rationale for declaring war on Mexico.

I also wanted to teach students that both Indigenous people and enslaved Africans struggled heroically and courageously to defend their freedoms. There was resistance, uprisings, and many ways that oppressed people fought back. Non-white freedom fighters were heroes too.

These I taught alongside the stories of the colonial struggle for freedom from Great Britain. The struggle for freedom among Euro-Americans was no different than the struggle for freedom among African Americans. Freedom is freedom, regardless of who is fighting for it.

I wanted to dispel the myth of the “Lost Cause” narrative of the Civil War. I taught my students that enslavement was indeed the major cause of the Civil War. The historical record is clear.

I revealed what the life of an enslaved person was like. I spent one entire class session discussing the treatment of enslaved people, slave trading auctions and markets, the domestic slave trade, and the brutality of the system. Using first-hand accounts and stories, I tried to bring the lives of enslaved people to life for my students. These stories were of real people who had real names, hopes, trauma, fears and faith. These are the hidden stories that don’t appear in our textbooks and curriculum…left out of the narrative because they interrogate and impeach the grand illusion of the nobility of the white-American expansionist project.

Teaching about forced labor and contributions of enslaved people to the success of the market-capitalist economy put the efforts of Black people as much at the center as Euro-Americans. Black enslaved people built the cotton economy which even northern states relied on, erected most of the buildings in Washington DC and dozens of college buildings, court houses, government buildings, banks, railroads, and other infrastructure. It wasn’t hard to build a wealthy country when 4 million of the laborers were unpaid, forced workers.

In other words, the adventures of Euro-Americans were not always front and center in this story. I put the lives of those who were enslaved, oppressed, and marginalized at the center. It is an approach rarely taken in history courses.

I found out quickly that white supremacy doesn’t like to be de-centered or upstaged in the American story. White supremacy is a very selfish ideology that loves to have all the attention focused on its great white heroes, despite their internal contradictions.

For instance, I taught about the American Revolution and the exploits of George Washington and the other founders of the United States. They were great men, but I also included the strained contradictions that existed for these men of the Enlightenment who said that all men are created equal, yet held and sold slaves. In some cases, raping them.

You can’t teach about the writing of the Constitution of the United States without dealing with the sections that supported the institution of enslavement like the three-fifths compromise. The compromises accepted by the founders concerning enslavement showed the inherent contradictions within the foundations of the country, which led to a deadly disaster 80 years later in the Civil War.

Nothing that I taught my students was historically untrue or inaccurate. What was different than what I had done in the past was change the emphasis from Euro-Americans to those who played an equally important role in the development of the nation. I de-centered the “white” story and centered the story of other groups who built the nation: women, Indigenous tribes, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latino people.

Howard Zinn called it “The People’s History.” He makes this comment in his book:

“And then there is, much as we would want to erase it, the ineradicable issue of race. It did not occur to me, when I first began to immerse myself in history, how badly twisted was the teaching and writing of history by its submersion of nonwhite people. Yes, Indians were there, and then gone. Black people were visible when slaves, then free, and invisible. It was a white man’s history.” (p 685)

My goal was not to allow the narrative to be a white man’s history only, or to allow those non-white groups to disappear. The American story belongs to all of us; the good, the ugly, and the downright inhumane and the glorious and triumphant.

An honest account of the past is the only path toward healing and reconciliation.

The students, over the past year, in the main, responded to the new approach positively. It was new for them. The history classes they had prior to that point were white-centered narratives. I warned them from the beginning this would be different.

I’m going to share some of the responses I received from students about the class. I was encouraged by the responses, both the good and the critical. Yes, some students were not happy or were critical with the different lenses.

For example, I had a student whose parent is a state representative. (Enter the “history wars”). That student reported to the campus administrator that my classes were “too racial” or something to that effect. I shared my curriculum with the campus administrator and received their full support. The student's parent was continually scrutinizing my materials, I assume, looking for “woke” teaching.

It had nothing to do with being “woke” (whatever that is), but it had everything to do with being honest and forthright in telling the American story…ALL of it.

For those predisposed to believe that teaching history is a process of creating “patriots” who see nothing wrong with the past sins of the country, my approach will certainly cause some heartburn.

My approach reverses the context of “patriotic history.” If you put the word “patriotic” in front of “history” it spells…propaganda. True patriots are those who love the country and want to see it live up to its ideals, and therefore, teach the whole story, not white-washing it to make it fit some mythological framework of American exceptionalism.

The United States isn’t exceptional because it is somehow inherently superior to all other countries or cultures. It is exceptional because of its capacity to self-correct and accept responsibility for its egregious actions, make better policies, and move on to expand the horizon of human rights to more and more people. That is exceptional and that is the American story.

I asked students in a non-graded survey for their reaction to the course. The question was:

Describe how this study of US History differs from your past experiences in learning US History.

Here are a few of the responses:

Slavery was definitely discussed a lot more and a lot deeper than any other history course I've taken. It was taught from real accounts and actual stories, making it both more accurate to real history and less watered down.

Another student wrote:

I'd never heard of some of the horrible things enslaved people went through until learning their history from this course; it gave light to the "hidden" history of slavery in America, the stuff that's unfortunately purposely not taught in other courses.

In some of the class exercises, I asked students to take on the role of different people in the period of study. They were forced to make decisions and judgments based on their various historical viewpoints, whether they agreed or not. Here was one student’s reaction to that experience:

This history course was different in its focus on thinking like the people or groups of certain periods. We did exercises that forced us to pretend to make decisions as political groups from different points in history that we usually disagreed with, which helped me understand better how certain things came to be. Pretending to be a white, Republican government official from the 1800s or a Confederate troop leader really helped my understanding of the topics, people, and events that took place in those times. While my opinion of those people didn't necessarily change, my perspective of history certainly did. I now insert myself into others' shoes when I'm reading history, which gives me more insight into how those events unfolded. It was thanks to this history course that I do this now.

I loved this student's conclusion about being able to insert themselves into “others’ shoes,” which is another way of saying, they developed empathy. That was one of the major outcomes I was looking for.

Another student commented on the different “lenses” they were asked to use in analyzing historical events. By lenses, I mean a political lens, economic lens or social-cultural lens.

One of the most important lessons I've learned throughout this course is that history is not fixed; it can be interpreted in many different ways depending on the lens through which it's viewed. Understanding that we must use these varied lenses to gain a more balanced and comprehensive view of historical events has been a key takeaway for me. Additionally, I've come to realize that almost every event in history has both positive and negative aspects. More often than not, these events lead to outcomes that shape both sides of the narrative.

That was a brilliant observation…Another student commented on varying lenses this way:

Although I haven't taken many U.S. history courses in the past, the ones I have taken primarily focused on one perspective. This course, however, has been different. Throughout it, I've had the opportunity to explore a variety of historical lenses and perspectives, which has provided me with a more well-rounded view of historical events and how they impacted different groups of people in different ways.

Not all students appreciated the de-centering of the white story. I am glad this next student felt free enough to share their perspective. It can be disorienting to have one expectation about what you might be learning, only to have someone throw you a curveball. I’m always open to hearing from students and their suggestions for how to improve my course and my teaching. In this case, it is also reaffirming that I was doing the right thing.

Discomfort is not a disqualifier to learning, sometimes it opens new avenues for having prior assumptions challenged.

The instructor knew very much about the material, but the material was a bit misleading. I thought I was going to get a well–rounded history course but instead got a very political history of slavery. Slavery is very important to learn about, don't get me wrong, but that was almost all we learned about, talked about, or discussed. 95% of assignments had to do with slavery, and the subject worked its way into every lesson. It seemed... obsessive. It was interesting, and the professor certainly knows everything there is to know about slavery, it just felt inappropriate for what I was told I was getting. The history of slavery to 1877 might be a more fitting name... That aside, it was very interesting.

This student had a perspective that I very much appreciate. Being confronted with a non-white centered historical narrative can feel very disorienting, almost like a betrayal. To this student the change of emphasis “seemed obsessive” as if the white-centered narrative isn’t? But that is the point…white-centered history is so normalized and innocuous that anything other than that seems “obsessive.”

Mission accomplished…I will continue to teach the truth, balance the narrative, provide multiple lenses through which to view the historical record, and encourage critical thinking…that…is history education.

I am a proud member of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. There are over 80 writers who are some of the best in the business. You can find the whole list of Collaborative Writers here.

Your teaching is the way American history should be taught.